3 Messed Up Things People Never Notice About ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’

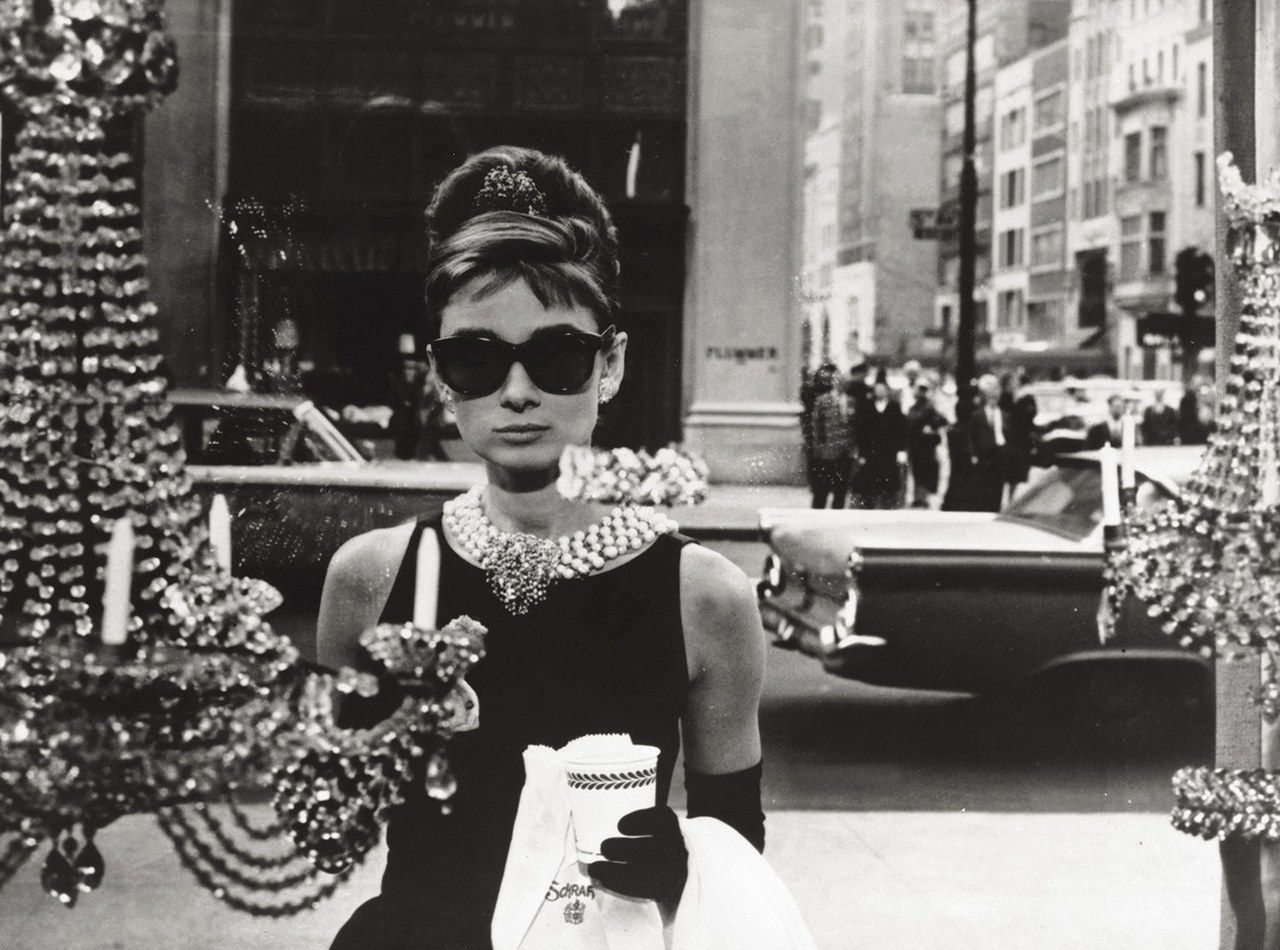

In some circles, it’s become a bit of a cliche to cite Audrey Hepburn as a style icon, especially because it’s often Holly Golightly—her character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s—that’s actually the icon they’re referring to.

We bet you’ve seen this poster before.

Odds are, you’ve seen the above photo everywhere—in dorm rooms, in framing stores, on Pinterest. I totally get it—the image is inherently chic and classic—but what I have a harder time grasping is the misconception that surrounds the movie’s plot. I’m willing to bet a fair amount of young women pinning and pining over that iconic photo haven’t actually seen the movie. Or if they have, they’ll describe (loosely) as follows:

A party-girl socialite named Holly who can’t be tied down falls for the golden-haired novelist who moves into her building. They run around New York being young and carefree, then they make out in the rain. She has a cat named Cat and she looks amazing and really thin, the end.

While some of those points are valid, that movie just doesn’t exist. It’s a version watched through a sheet of pink tissue paper. As someone who has seen Breakfast at Tiffany’s more than a few times and have spent a lot of hours thinking about the movie beyond its aesthetics, I believe most fans might not realize three obvious—and vital—aspects of the film.

1. Holly Golightly is actually a criminal and a call girl.

Technically, Holly isn’t a carefree spirit subsisting on cigarettes and good times—she’s a runaway hillbilly child bride named Lula May who’s too damaged to have a deep emotional connection with anyone but her brother.

Also, Holly charges men for “conversation” and asks for “powder room” tip money, and they follow her home begging for sex. It’s not clear in the film whether or not she sleeps with any of these guys, but she finds income in much the same way a certain kind of sex worker would: She picks the richest man she can find and charms him into submission. Fact: Truman Capote, author of the novella on which the film is based, likened Holly to an “American Geisha,” so take from that what you will. He also wanted Marilyn Monroe for the film because this character’s charm isn’t (only) her je nais se quois; it’s her overt sex appeal.

There’s nothing amoral about what Holly’s doing, and it’s clear her charm is a foil for her loneliness, insecurity, fear, and ultimately, instability. That said, it’s interesting to me so many young women idolize this character. Maybe she was empowered for her time, but she’s also operating almost completely as a cypher for men’s desires; so can we put the mantle of early feminist role model on slightly less coquettish shoulders, please?

I’m certainly not the first to talk about this—it’s a point of conversation around the web. The book and film are both all about society roles; you can frame Holly as a step backward, a master manipulator of the patriarchy, a feminist icon, or at least, an icon for feminists, and even an everywoman.

What’s impossible to ignore is that Holly is also a criminal. Her steadiest source of cash is relaying coded messages from an imprisoned mobster to the outside world. Which would all be well and good, except that Holly literally has no idea that that’s what she’s doing. It’s not that she’s dumb, she’s just glaringly uneducated.

Again, not a moral defect. But again, let’s all pay close attention to the woman behind the Little Black Dress.

2. Paul Varjak is no angel, either

Paul is a writer. A good writer? We don’t know; we don’t meet anyone who’s read anything of his. We do see a few lines of a piece he writes inspired by Holly, but in any case, he doesn’t spend very much of the movie “at work.” Instead, everything in Paul’s life is paid for by an older, married woman with whom he routinely has sex and for whom he appears to feel little affection. She leaves him cash on his nightstand and even offers to bankroll a weekend away for him and Holly. She talks about him, to his face, like he’s an employee or maybe a piece of meat. Homeboy gets paid for sex.

Again, not a “bad” thing. He gets a sick apartment; the older woman gets hot sex with a good looking guy. It’s a win-win. But let’s not be naive and pretend this doesn’t complicate the love story. Paul’s main attraction toward Holly seems to be that she’s even more screwed up than he is, and he wants to save her. He literally says he wants to help her. Help her what, Paul?

It’s kind of cool and role-reversal-y to see a “kept” man falling for a (seemingly) strong-headed commitment-phobic woman instead of the other way around. But again, let’s all think before we romanticize the Holly/Paul relationship. They don’t meet because of the sparkling magic of Manhattan; he moves into her building because his lady needs a sex pad. Technically, a sex pied-à-terre.

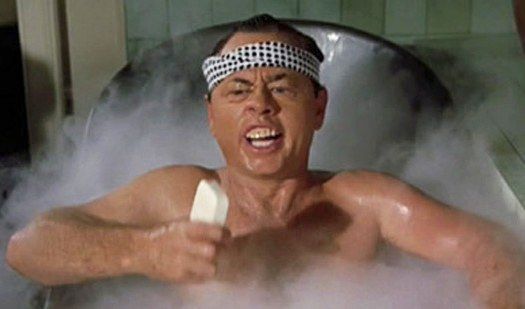

3. This movie is racist, folks

areyoufuckingkiddingme

This is the big one. The part of BaT people seem to completely forget when talking about the film’s appeal. How many girls who visit New York begging to be taken to Tiffany’s do you think understand that the third-biggest star in the film is Mickey Rooney wearing fake teeth and pretending to be a Japanese man?

He’s the only nonwhite character in the film, and he’s played by a white man. And he’s a stereotype in literally every way that could have easily been cut from the plot, but was kept in, presumably, for comic relief. Shudder.

Sure, it was a different time—I’m not going to hold a movie from 1961 to 2016 standards. But—and this is a big but—if you’re going to list this movie among your favorites, you have to contend with the fact that there are some pretty unsavory undertones.

To me, these overlooked aspects are critical to understanding the movie. Holly’s ambiguities, flaws, and layers make her a much more interesting protagonist than the PYT we see on so many Pinterest inspo boards. Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a weird, gorgeous, difficult, fascinating, dark film—and it’s all the better for it, but if you’re looking for something aspirational that you can watch purely for aesthetics, well, there are thousands of other films to choose from. So next time you claim this is your all-time favorite movie, I hope you’re able to back it up with some of the films flaws, and not just cite the fashion as the reason.

If all you want is a sweet, pure Audrey Hepburn-in-love tale, try Roman Holiday; it’s great. And if you just want the misadventures of a fun-loving gal-about-town in New York, Party Girl is criminally under-seen.

More from our partners: