The Oral History of Lilith Fair, As Told By the Women Who Lived It

Imagine many of the country’s most influential women all gathered together to stand up for gender equality on a national stage. There are stars performing before a massive crowd, Planned Parenthood booths (along with protesters), and reporters from news outlets analyzing what this event says about the state of women’s rights. Sounds like a scene from the Women’s March on Washington—but it actually occurred 20 years ago this summer with the debut of Lilith Fair, a music festival designed to give women the same lucrative touring gigs as men. Cofounded by singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan, this multicity tour broke new ground, from the all-female talent lineup that promoters said would never work, to the controversies it ignited in the media about race and feminism. Here McLachlan and some of her fellow Lilith performers talk candidly about a cultural movement lauded by fans for its feminist ideals and lambasted by critics for its lack of diversity. And a new generation of performers reflect on the legacy of Lilith Fair and why their own fight for equality in the music industry continues.

The 1990s were a strange time for women musicians. On the one hand, the singer-songwriter movement was ushering in young female stars like Tori Amos, Tracy Chapman, and McLachlan. But women still had to fight harder than the guys for radio airtime and touring slots. In 1996, McLachlan was 28, still climbing the charts with singles from her breakthrough album, Fumbling Toward Ecstasy, and struggling to write the follow-up, Surfacing, which would become her best-selling record. Searching for inspiration, she organized a mini festival—a gathering that would ultimately morph into Lilith Fair.

SARAH McLACHLAN (singer, cofounder of Lilith Fair): We looked around [at other tours] and thought, Wow, they’re just full of men. And yet there’s all this amazing music being made by women right now. So why is that not being represented?

BONNIE RAITT (singer): Promoters felt in pop and rock you couldn’t put women on the same bill.

TERRY McBRIDE (CEO of Nettwerk Music Group, McLachlan’s longtime manager, and a cofounder of Lilith Fair): Sarah had writer’s block, so I was trying to get her to do a couple of weeks of summer shows and enjoy herself. She put a challenge to us. “OK, I’ll do it if you can put together a show that’s all female artists.”

McLACHLAN: I thought, Let’s ask a bunch of gals if they want to do some shows. We did three shows. The biggest one [in Vancouver] was like 10,000 people. We thought, Holy crap!

SUZANNE VEGA (singer): It went really well except for one of the truck drivers had a run-in with police. The truck was impounded, including all of our equipment. We were playing [outside of San Francisco] and had to postpone to the next day.

McBRIDE: Sarah had a great time and said, “I’d like to do that next year.”

McLACHLAN: I got to listen to all these amazing women every night and be part of a bigger community. It felt really good.

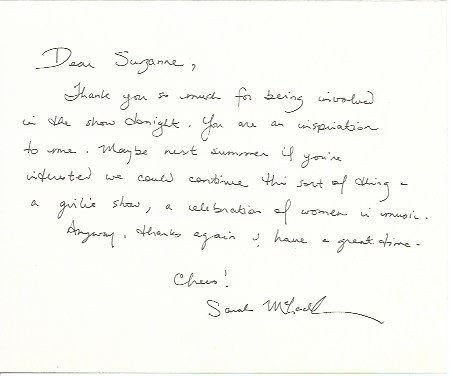

VEGA: At the end of that tour, I got this lovely note from Sarah, saying, “What a great run. I’m thinking of having a kind of girly show next year.” That girly show turned into Lilith Fair.

MARTY DIAMOND (talent booker and a cofounder of Lilith Fair): We knew we had something. Sarah felt women didn’t have a real presence in Top 40 radio and wanted to build that spirit up a little bit.

A letter from Sarah McLachlan to Suzanne Vega. The “girly show” would become Lilith Fair.

McLACHLAN: I’d never felt an ounce of sexism from any of the guys at my record label. The first time I felt sexism was the pushback from radio stations [in the midnineties]. They’d say, “We added Tori Amos this week, so we can’t add you.” Or: “We added Tracy Chapman this week, so we can’t add you.” And I’m like, “We’re doing completely different [things]!”

VEGA: It’s not as if anybody was as blunt as that to me, but I knew the quota of male-to-female artists [on the radio].

MESHELL NDEGEOCELLO (singer whose new album, Ventriloquism, will be out this fall): I dabble in the jazz world, which is male-dominated. [If you had two women playing together], it became a shtick. It becomes a “girl group,” and it has to be something cutesy. That’s hard to contend with.

McLACHLAN: We made the plan to do it full-on the next summer. And promoters were saying, “You can’t put two women on the same bill. People won’t come.” I was like, “Well, we’ve done it! So you can either support us or get left behind.”

McBRIDE: It was a foreign concept to most promoters.

McLACHLAN: I put together a huge wish list, then I handed it off and said, “OK, go see who’s in, who’s gonna say yes.”

McBRIDE: The first year was difficult. Lilith hadn’t been proved. The agencies were like, “I’m not going to put my megastar there. I don’t believe it’s going to work. No one’s going to show up.”

McLACHLAN: Paula Cole [said yes immediately]. Lisa Loeb. Emmylou Harris was in like a dirty shirt right away.

McBRIDE: It was really difficult to get a country headliner, an urban headliner, and a pop headliner.

Lilith Fair cofounder Sarah McLachlan at her music studio in West Vancouver in April 2017

McLACHLAN: I was talking to a friend about the concept and said, “I need a name.” She goes, “Have you heard the story of Lilith?” In Hebrew mythology Lilith is Adam’s first wife, before Eve. He asked her to lie beneath him, and she said, “No, we’re equal.” She left, and she was made into a cautionary tale. I thought, Perfect protagonist! Obviously words are important to me, and Lilith on its own didn’t seem like enough. I loved the play on words of fair being the sort of old-fashioned fair, and fair being equal.

AMBROSIA HEALY (publicist for Lilith Fair): I don’t know that people thought Sarah was crazy, but it was a new idea for certain. I remember sitting down with her team to figure out the Lilith Fair mission statement. The intent was to create an inclusive and supportive community based on the celebration of women in music.

McLACHLAN: Terry really wanted corporate sponsors. I said, “I want them to do something for the community.” We wanted to leave something beyond the music, which is [why we donated] a dollar for every ticket sale to a local women’s shelter.

McBRIDE: Those checks were sometimes the difference between the shelters staying open or closing down.

SHERYL CROW (singer whose new album, Be Myself, is out now): The fun thing about it was, it redefined what the [DJs and] promoters believed about female touring. It immediately sold out everywhere.

McLACHLAN: Lilith was just this beautiful idea where women could all come together and be stronger as one united force. We didn’t have to compete [with one another]. We came from a place of love, joy, and a need to create.

Before Lilith Fair began, the most well-known female-driven music festival had been the Michigan Womyn’s Festival, a radical-feminist gathering. So Lilith’s 35-city tour, featuring McLachlan, Crow, Tracey Chapman, Jewel, and more than 60 other female acts, was unprecedented. At the first show in George, Washington, Lilith drew 27,500 fans (most of them women), a few vocal critics, and an SNL parody featuring a character named Cinder Calhoun singing a song called “Sausage of Pain.”

CROW: One of the things that made me so excited was that I was not only going to get to see people I wanted to see play but getting to build a relationship with the people during the summer.

VEGA: I was the first one on the main stage [at the Gorge Amphitheater]. It really felt like a momentous occasion. My first song was “Rock in This Pocket,” a David and Goliath song from David’s point of view. I felt like, “This is a rock at the head of the mainstream corporate thinking.”

INDIA ARIE (singer whose new album, SongVersation: Medicine, is out now): I wasn’t signed, and I was known only in the Atlanta music scene. So I really wanted to do Lilith Fair [when they asked me].

SKYE EDWARDS (lead singer of Morcheeba): My understanding was that it was all solo female artists. And I was obviously a female, but I was in a band with two guys. So [when they booked us] I kind of felt like, “What the hell? They want us? How do we fit in there?”

ANN POWERS (music critic): My first impression was, there was a field full of women music fans, sharing blankets, sunbathing. And there was this overwhelming feeling of safety and confidence. No one was going to wolf-whistle or cop a feel as you walked by or shove you down to get to a mosh pit. Here was a space where the violence and disrespect that could loom at other concerts was absent. That was as important to me as the performers onstage.

Tracy Chapman, backstage at Lilith Fair.

CROW: You would be surprised at how many guys were there [in the audience] too. It really wasn’t just all women.

DIAMOND: I saw a bunch of college-age guys, and I said, “Why are you here?” They said, “Dude! This is where the girls are!”

NDEGEOCELLO: Touring with all women was communal. I didn’t have anyone barking at me at sound check. I know that sounds stereotypical. But maybe it’s [also] because Sarah is Canadian. It was just like a really chill vibe, you know? I’m sure if I did a festival with Courtney Love as the head, that would be a different vibe.

ARIE: [Folk singer Victoria Williams] had some sort of a neurological disease. [Williams has multiple sclerosis.] She had tremors in her body. She was standing by the side of the stage, and Bonnie Raitt said, “Hey, you want to come out?” And she walked onstage with a harmonica and started playing. I remember thinking, What is this lady going to do with this harmonica? Her hands are shaking! She played beautifully.

HEALY: Everybody flew out to Washington State to cover this thing. Lorraine Ali was there to do a big feature for Rolling Stone. Christopher Farley and David Thigpen came from Time magazine. VH-1 and MTV were there with crews. This is the middle of nowhere, two hours outside of Seattle.

LORRAINE ALI (music journalist): I remember at the time thinking, in my snarky, rock-critic-y way, Why does this have to be so crunchy and folky? How come you don’t have Courtney Love or 7 Year Bitch or Elastica? Why isn’t Lauryn Hill or Missy Elliott on this? Going in, [a lot of women at Rolling Stone] had reservations about Lilith because it was taking the most passive thing in popular music that women were doing and putting it forth as the united front of women in music, and it wasn’t united at all. It wasn’t inclusive of everything that was going on, and it wasn’t showing the innovation in music.

POWERS: Do I remember specific ways that Lilith was covered that were sexist or just unfair? Well, nicknames like Breast Fest were certainly unfortunate!

McLACHLAN: All of a sudden [the press was casting me as] the daughter for the new feminist revolution, and I’m either too feminist or not feminist enough, depending on who was firing the questions. And every day it was like, “Why do you hate men? Why don’t you have men on the bill?”

MAYNARD JAMES KEENAN (lead singer of the all-male band Tool): I asked our booking agent to request an offer to play. He did. They declined. I wanted the “thank you but no thank you” letter to frame. Never got it.

NATALIE MERCHANT (singer-songwriter whose album, The Natalie Merchant Collection, is out now): [The questions] were exhausting. I thought, We’re just people making music, you know?

McLACHLAN: I grappled with the fact we were being so successful [while] people were saying negative things or trying to pull us down. We got a lot of flak for being a white-chick folk fest. [Only two of the headlining acts were women of color: Tracy Chapman and India Arie.]

McBRIDE: We knew the media would come at us hard for that. And we tried, but I think you should question the artists who said no.

McLACHLAN: That was not for lack of trying. We asked everybody.

EDWARDS: I didn’t pick up on [the lack of diversity]. I’m a black woman fostered by white parents. I live in Surrey, [England,] and there’s not many black people. I don’t feel like a “black artist.” I’m a singer-songwriter that happens to be black.

POWERS: In truth, Lilith wasn’t a genre-spanning women’s music festival. It was a singer-songwriter festival focused on women. The question is, Why is the category of singer-songwriter cast as white?

Paula Cole playing to a sold-out audience in George, Washington, in 1997

ALI: I had taken the [tour] bus down [from George, Washington] to the next stop [in Salem, Oregon] with [jazz artist] Cassandra Wilson, and she was upset because they put her on the second stage. She was unhappy about it, and she was justified. Most of that bus ride was spent talking about how she got f-cked over. The more I think about it, the Cassandra Wilson thing probably was cut along color lines too.

McLACHLAN: That was the thing we had to defend more than anything else, more than our feminism, more than our choice to have just women. It was: Why you don’t have more black artists, more R&B artists, different kinds of music, representing everybody?

ARIE: I know why they called it the white-chicks folk fest, but I love that music.

McLACHLAN: I don’t think Perry Farrell was taken to task for those things [when he put together Lollapalooza]. We were doing something that really hadn’t been done before, so anytime there’s anything new happening, there is the desire to tear it down or find holes. Especially if you’re trying to do something good. It pisses people off.

Lilith earned $16 million gross in 1997, making it the most successful touring festival that year. So by 1998 many more artists wanted to perform. There were three months of back-to-back tour stops—and a more diverse range of musical styles, including artists Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliott, and Erykah Badu.

McLACHLAN: Lilith was becoming this crazy-big phenomenon that everybody was so excited about.

McBRIDE: It became easier [to book artists] in years two and three.

McLACHLAN: [The second year] we had to show managers and record labels that we could be diverse and still make it work as a festival.

POWERS: The second- and third-stage artists were always my favorites. I saw so many people for the first time at Lilith.

NDEGEOCELLO: When Erykah Badu played, I had to hold her baby for the first two songs. She was like, “Here, hold Seven. I have to go on.”

McLACHLAN: [Erykah] was pretty quiet. I mean, she was intimidating, holy crap. She’s like a queen, very regal.

CROW: I used to go out and watch other bands. Chrissie Hynde and I would put on these hats that had wigs attached to them, and we would go sit out front and no one would recognize us.

McLACHLAN: When I first met Chrissie, she was pretty aloof. A little bit older, very established, rock ’n’ roll, right? And she was like, “You little folk bitches!” So the last night, I had a hot-pink tube top on, and I thought, I need to do something to freak her out. So I went out onstage, and I flipped her my boobs. Her drummer dropped his sticks. I brought Chrissie Hynde to her knees!

Paula Cole, 1997

MERCHANT: I saw all of these performances from the side of the stage. I remember Erykah Badu. I remember Meshell Ndegeocello. I remember running to see Morcheeba every night. And Sinéad O’Connor was amazing.

ASHWIN SOOD (drummer and Sarah McLachlan’s then husband): We all worshiped Sinéad O’Connor.

McLACHLAN: Oh, Sinéad, that brat! [Laughs.] I remember I had food poisoning right before the show. So Sinéad went out there and [told the crowd], “Oh, Sarah’s backstage puking. It’s probably from morning sickness.” Then there was a big rumor that I was pregnant. The bugger.

VEGA: I remember seeing Missy Elliott in her [inflatable] suit, running up the aisles going, “Y’all better show me some love because it’s really hot in here!”

McLACHLAN: We got to hang out with all of these amazing musicians from all of these other bands, you know?

RAITT: On the last day of Lilith, my tour manager went out with some of the male crew to the thrift stores and bought sundresses for all the crew, and did the load-in and load-out in work boots and sundresses. They came out at the end of “What’s Going On” and did a chorus line like the Rockettes. For the men to be in dresses with no explanation was badass.

SOOD: Christina Aguilera was just breaking [in 1999]. She was playing on this little “village stage” at Lilith. And watching someone like that for the first time—someone whom nobody had heard of—my jaw was just on the floor.

LIZ PHAIR (singer-songwriter): One of the most vivid memories for me was joining the other performers onstage at the end of Sarah’s set for a communal song [at the end of the night]. The impact of sharing a musical moment with icons—exceptional artists whose voices I’ve loved and new artists I’d discovered on tour—left an indelible impression on me. Imagine blending your voice with voices so familiar to you and looking out into the darkness, where people were waving lights and singing along, and you get a sense of the exhilaration of the moment.

POWERS: Lilith was a great vehicle for the discovery of women artists, something that wasn’t so easy when women weren’t being included on other festival bills.

HEALY: Sarah changed popular music for a few years. Lilith came out during a time when all the music was male-dominated. Then it went the other direction, where it was all women. Suddenly, if you were a male rock band, you weren’t getting the same attention on the radio.

The summer of 1999 featured more R&B acts, the small-stage debut of Christina Aguilera, and a surprise performance from Prince. But suddenly the same things that made Lilith a success—including its goal of catering to all women—started to work against it.

McLACHLAN: After three years we were at our peak. [Lilith Fair] was changing the way the industry was looking at women. [They started to see] us as a force that they didn’t see before.

POWERS: Sheryl Crow played [in Jones Beach, New York], and she rocked so hard during her set. It’s the best set I’ve ever seen from her. She covered “Sweet Child o’ Mine” and invited Chrissie Hynde and Meshell Ndegeocello onstage to guest—the camaraderie of the tour was clearly pushing her in great directions.

SOOD: I was playing percussion in Sheryl Crow’s band. At that time Prince was hanging out with Sheryl and would show up at her shows. Earlier in the day, we heard Prince was coming to the show, and then Sheryl had gotten us all together and said, “Hey, so we’re gonna do a little rehearsal in the dressing room.” And at this point in Prince’s career, he was going by The Artist. So we all go to Sheryl Crow’s dressing room, and we put a superband together to do her song “Every Day Is a Winding Road” that Prince was going to play guitar on. So I get into the dressing room, and there he is in a gold lamé suit from head to toe. He’s wearing gold seven-inch heels. And Sheryl introduces me: “This is Ashwin. Ashwin, this is The Artist.” He looks at me, and the only thing that comes out of his mouth is “You must be The Husband.”

TEGAN QUIN (singer-songwriter of the band Tegan and Sara): Sara and I played in 1999. Lilith Fair came to Edmonton that year, and we played on a village stage. We got a 20-minute set. It was pouring rain, and there was a woman sweeping huge pools of water. [Laughs.] There was no one there.

SARA QUIN (singer-songwriter of the band Tegan and Sara): I was thinking, Well, this is where the people would go if we were even remotely popular. [Laughs.]

TEGAN QUIN: We were genuinely excited. A bunch of our friends and my mom stayed afterward and watched all the big acts. I mean, it was really exciting.

McLACHLAN: At some point we had, like, 133 [acts] out on the road with us. So there was always a drama. An artist wasn’t showing up or something was happening. It was a crazy, frenetic day every day.

KAREN EDEN (lead singer of Eden A.K.A., which will release a new album this fall): It [became] a little more corporate. I have photographs of us standing around different booths.

McBRIDE: Sarah was a big supporter of Planned Parenthood, and there was pushback [against their booths] in certain parts of America.

McLACHLAN: One of the biggest lessons I learned was, You cannot be everything for everybody. I tried! And I realized that I will continue to fail if I try to please everybody. Which is kind of where I got to when pro-life [activists] were picketing [our booths]. I finally stood up and said, “You know what? I don’t agree with you, and I don’t want you here, so you can go stand outside and picket. Sorry, it’s my festival, and I get to choose.”

McBRIDE: For three years Lilith was the biggest traveling festival inside North America.

EDEN: But in 1999 the Latin-music thing came on board. Ricky Martin exploded. Suddenly it was all about J. Lo. So the singer-songwriter vibe that Sarah made so popular had had its day. It was still a great turnout, but it had a different energy.

McLACHLAN: Everybody wanted more. I was like, “No, now is the time to stop. Let’s leave on a high note.” I was exhausted. The record label wanted a new record. I said, “I’ve been on tour for three years! I’ve got to go home. And I have to have a life. People have been having babies and getting married and divorced, and I’ve missed it all.” That’s the price you pay.

In the decade that followed the final year of Lilith Fair, pop and hip-hop acts largely replaced singer-songwriters on the charts. Music festivals exploded in popularity, thanks in part to newcomers such as Coachella and Bonnaroo. In 2010, after repeated requests over the years from artists and fans alike, McLachlan agreed to headline a revival, but it failed to meet expectations.

SARA QUIN: The original Lilith Fair, it was something my mom and her friends were excited about. I was a punk teenager taking drugs and going to raves. I was not listening to that music. When Sarah approached us about doing a few shows in 2010, we were like, “Sure, sign us up.” But I want to be included in all the festivals.

McLACHLAN: I was finishing a record [in 2010]. I left it completely to [Terry and Marty] to organize.

McBRIDE: Concert tickets were down—and it wasn’t just Lilith. The venues had become very difficult, with add-ons that drove a $25 ticket to be a $50 ticket.

McLACHLAN: All those women who came to see us now had mortgages and three kids and weren’t going to stand in a hot field for $150 all day. It flopped, and I take responsibility for that. It hurt when the press would say, “Your ticket sales suck, and nobody cares anymore.”

MERCHANT: But Lilith could still happen today. And it probably should.

McLACHLAN: Lilith could work today, but Adele, Taylor, or Beyoncé would have to spearhead it. And when it comes to the ugly financials, artists aren’t getting as much money [from a festival] as they would if they went out by themselves.

ALESSIA CARA (singer): I was one year old [when Lilith began]. I heard about it as I got older, and I started watching interviews with all these great women that I looked up to, and Sarah McLachlan was one of them. Now we see women supporting other women, which is because of things like Lilith Fair.

McLACHLAN: I love Alessia Cara! I met her [at the Juno Awards], and I said, “You should be so proud of yourself for being such a great role model. The things you believe in, my girls are hearing it, and it really helps, because it’s a tough time for girls right now.” I have to pull down pictures of my daughter’s ass off Instagram every other day. It’s like, “Honey, is this what you want the world to see? Because that’s what they are seeing. You are f-cking smart, and you are a leader. Show me that on Instagram, you know?”

KATE NASH (singer whose new EP, Agenda, is out now): I think we definitely need all-female festivals because most of the festivals are predominantly male. It hasn’t changed.

SARA QUIN: Pitchfork did a survey of 23 of the top festivals this year, and 74 percent of the bills are men.

POWERS: Top 40 has changed somewhat, because there are so many major women stars, but it’s not as much as you’d think. When I recently looked at the Top Radio Airplay chart, there was one woman in the Top 10: Alessia Cara. There’s only one [female] rapper, Nicki Minaj, who gets significant airplay.

Alessia Cara, whom Sarah McLachlan calls the future of Lilith Fair. Says Cara, “We see women supporting other women because of things like Lilith Fair.”

BANKS (singer): Lilith Fair was an attempt to bring social change through cultural activities that empower women. That would definitely hold up today.

SARA QUIN: I don’t know. I look at a lot of festivals and think, I don’t want to pee in a trough, and I don’t want to wait for 45 minutes for a bottle of water, and I don’t want to stand next to bare-chested people and mosh and be sweaty. The only kind of festival I want to go to is where I don’t have to touch anyone, and I can be in a cold, sterile, modern environment and watch music. I basically just described my office, where I streamed Coachella last weekend.

POWERS: I think a new festival should be led by young women, be diverse at its core, and be more confrontational than Lilith. I see a bill with Solange headlining, with Angel Olsen, Anohni, Jamila Woods, Hurray for the Riff Raff, Xenia Rubinos, the rapper NoName. This is fun!

Despite global stars like Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and Adele selling out stadiums around the world and pushing their personal brand of feminism, the performers say the sexism Lilith Fair was designed to combat—and the racism it ignored—still permeates the industry.

SZA (singer-songwriter whose album Ctrl is out now): People write you off as being emotional because you’re a woman. But if you were a man and passionate, you’re either a d-ckhead or like, “Wow, you have so much power, I want to be like you.”

CARA: People don’t care what men wear or how they look. Unfortunately for women, [the music industry] is very visual and objectifying. The objectification of our bodies and using our bodies to sell things needs to change. A lot of this marketing stuff comes from men, so we definitely need [more] women behind the scenes.

ARIE: When you’re a black woman, you deal with both racism and sexism. I did a song with John Mellencamp, and I heard him say [in a 2017 interview] he left his label because someone there said, “I don’t know how we’re going to get him on the radio when he’s doing this music with these n—-rs.” I was like, Whoa. You don’t always see [racism] as blatant as this all the time, but that’s what the music industry is like.

EDWARDS: When I was releasing my first solo record in 2006, I was told by the A&R guy in the U.K., “They’re not going to play it. The box has been ticked by Corinne Bailey Rae.” They already had a black female artist with a British accent.

BETHANY COSENTINO (songwriter, singer, and guitarist of Best Coast): I shouldn’t have someone roll their eyes at me because I asked where the plug is on a stage I’ve never been on. It sucks to feel like a monitor guy is giving you attitude because he thinks you’re just some dumb girl that doesn’t know what she’s doing, and then you see your [male] bandmate ask the same question and he gives him a straightforward answer.

NASH: You’re treated like a child sometimes. You’re talked down to, and the attempt at control is quite strong.

SZA: We should let women be multifaceted. Women should be a boss without being [labeled] arrogant or being a bitch. They should be able to ask for what they want, they should be reinforced and supported without being the damsel. You should be able to have no limits.

TEGAN QUIN: Ever since we started in this industry, we were told you never want too many women on the same bill. You don’t want women opening for you. People encourage you to stay away from being pigeonholed as a female artist who only plays for women. Sarah did that at the height of her career, and that was a pretty bold move.

RAITT: There’s a generation of women that don’t remember Lilith, and it needs to be remembered. It wasn’t just about the music; it was crossing all kinds of issues and causes, and the whole vibe of it was so powerful. Remember that Lilith Fair was revolutionary.

McLACHLAN: I was raised with a mother who told me that I wouldn’t succeed, that I wasn’t good enough. Even at the pinnacle of my success, she’d come to a show, and there’d be, like, 10,000 people screaming. And she’d say, “I just don’t get it.” I think she had so little faith in herself and her abilities as a parent that she couldn’t imagine any offspring of hers could do so well. And all that did was drive me to push back. If someone says, “You can’t do this,” I’m like, “F-ck you! Oh, yes I can, and I will.”

Melissa Maerz has written for The New York Times, Wired, and Rolling Stone. Additional reporting by Ilana Kaplan.